Chuck Close’s 16th solo exhibition at PACE 25th street

September 11 – October 17, 2015

“Painting is the frozen evidence of a performance.” – Chuck Close

PACE Gallery launched its fall season with a vibrant and intense Chuck Close solo exhibition, 16th for the artist since the gallery began representing him in 1977. The compact bi-level installation is a triumph and I say that not solely because I’ve become an admirer of Close’s work ever since our first feature in 2012, but also because this exhibition feels charged with tremendous energy and reads diverse, explorative, and focused.

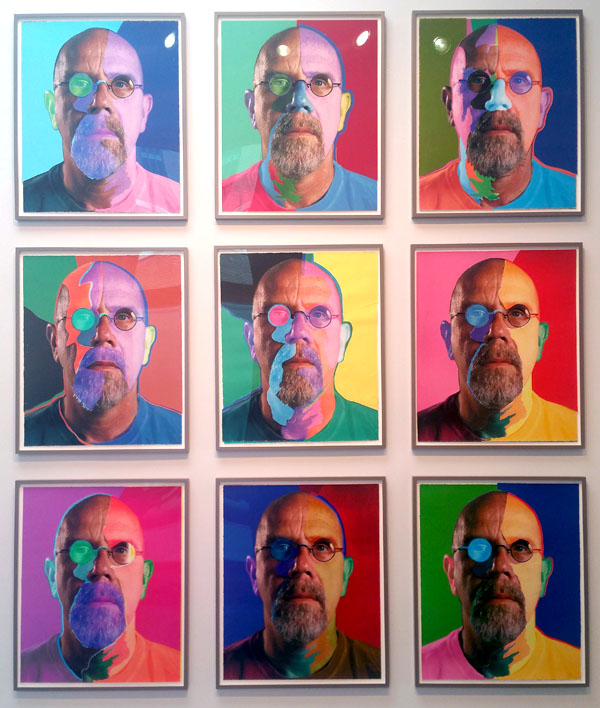

The exhibition opens with a Warhol-esque grid of 9 colorful collaged self-portraits. Each is a colorful layered self-portrait that you appreciate more if you come really close to the wall and look at it from an angle. From there on the viewer is treated to a series of some tightly cropped and some medium signature “pixelated” portraits that are renderings of the photographs you see at the start of the show.

As you wander through the exhibition make sure you go up the stairs located at the back of the gallery and see several older works done using pigment-tinted fingerprints!

So, why did Chuck Close chose portraiture as the genre of choice? It so happens that the artist suffers from severe lifelong prosopagnosia, a condition that is also called face blindness, a disability which he discussed in 2012 with Dr. Eric Kandel and Charlie Rose during a series of interviews titled The Creative Brain. This condition prohibits Close from recognizing people’s faces, which essentially means that even if he met someone many times before, he won’t recognize them. In a 2010 interview with The New Yorker Close said that he believes “the condition has played a crucial role in driving his unique artistic vision. “I don’t know who anyone is and essentially have no memory at all for people in real space,” he says. “But when I flatten them out in a photograph I can commit that image to memory.” The late psychologist Oliver Sacks has also revealed that he suffered from a milder form of the disorder.

So why has Close chosen a grid, which he calls his “pictorial syntax”, as the basic construction element for his portraits? The answer is actually a lot more utilitarian that philosophical. The grid allows him to deal with a large image “by taking small bites” and not feel overwhelmed by the whole task a hand. With time those squares became larger and larger which allowed him to use more colors within each section. In fact, the current exhibition at PACE features a couple of portraits created in two different size grids: a familiar visual for anyone familiar with photo editing software, but an unexpected one in a gallery environment.

- Self-portrait detail.

- Portrait detail.

What distinguishes the previous series of portraits from this one is what he did within each square. Gone are the horizontal, vertical and diagonal lines, ovals and circles that Close used to assemble his faces. Instead each square is filled wholly with layers of semi-transparent glazes in a restricted palette of red, yellow and blue: the selection that serves as the show’s title.

From the gallery:

“Close abandons the expressionistic brushstrokes that have characterized his paintings since the 1990s. Rather, he applies multiple thin washes of paint in each cell of the grid, layering red, yellow and blue until they accumulate into extravagant full-color images.”

From the artist’s bio: Chuck Close (b. 1940, Monroe, WA) is renowned for his highly inventive techniques of painting the human face, and is best known for his large-scale, photo-based portrait paintings. In 1988, Close was paralyzed following a rare spinal artery collapse; he continues to paint using a brush-holding device strapped to his wrist and forearm. His practice extends beyond painting to encompass printmaking, photography, and, most recently, tapestries based on Polaroids.

This article © galleryIntell